Protecting Graphical User Interface (GUI) under Indian National Design Policy

Graphical User Interface (GUI) was first developed by Xerox Corporation in the late 70’s. Steve Jobs was the first one to recognize its commercial potential. Identifying its true value, the concept of GUI was incorporated in Apple’s operating system Lisa. Later on, Microsoft introduced the same concept in its Window operating system. Quite expectedly, Microsoft was immediately sued by Apple, which in turn was sued by Xerox. The lawsuit was eventually settled amicably between all the 3 parties.

With the advent of technology and inclusion of electronic devices in our daily lives, GUI has become an integral and indispensable part of the software product market. The following article explains the current protection provided to GUI in India under the Designs Act, 2000, National Design Policy and the loopholes in the act with the evolving times.

GUI is an interface that enables a user to interact with a computer device or other electronic devices, such as machines, smartphones, smart watches, etc., through the use of symbols, icons, menus, pointing devices etc., displayed on the screen of that device. It not only provides end user functionality, but also projects the “look and feel” of any interactive electronic device. Thus, it has gained importance in the world of software products, as it decides the user efficiency of a product, as well as the look and feel factor as an aesthetic difference between competitive products.

Recently, in a controversy involving Zoom (a video conference platform) and JioMeet, Zoom considered admitting a legal action against JioMeet for allegedly projecting a similar user interface of its platform. However, Zoom only contemplated a copyright infringement suit as it did not have its GUI registered as a design in India.

Table of Contents

Legislation and its Objectives

In India, design registrations are controlled by the Designs Act, 2000 and related Designs Rules, 2001. Back in 2006, a design registration under the Act was granted to Microsoft for its icons and screen displays. This set a precedent for years ahead and design registration was granted to GUIs in some cases. Subsequently in 2007, the government launched the National Design Policy, with the objective of creating a “design-enabled Indian industry”. By now the industry was brimming with confidence and was in need of a holistic protection for designs – both tangible and intangible.

To execute the aims of the National Design Policy, the Design Rules were amended in 2008 to comply with global classification of goods and introduced the ‘Locarno Classification’ in the Indian Design Law. The 2008 amendment added a new class ‘14-04’ titled as ‘Screen Displays and Icons’ and introduced the registration of GUIs in India. These developments showcased a clear intent of the law and policymakers to make India a GUI protecting territory.

The initial promises, however, were short-lived, as regulators began to scrutinize closely citing interpretation of new section in the law.

Shift in Positions of GUI Protection in India

Despite the prior registration of GUI, like in the case of Microsoft, and the protection being provided by the Design Rules, the Indian Design Registry has been hesitant and reluctant in granting registration to GUIs. The Registry is of the opinion that GUIs do not qualify as designs under Section 2(a) and Section 2(d) of the Act, and hence cannot be granted registration. These sections of the Act define ‘article’ and ‘design’ respectively.

- Section 2(a) of the article states that, article means: any article of manufacture and any substance – artificial, party artificial, or partly natural, and includes part of an article capable of being produced and sold separately.

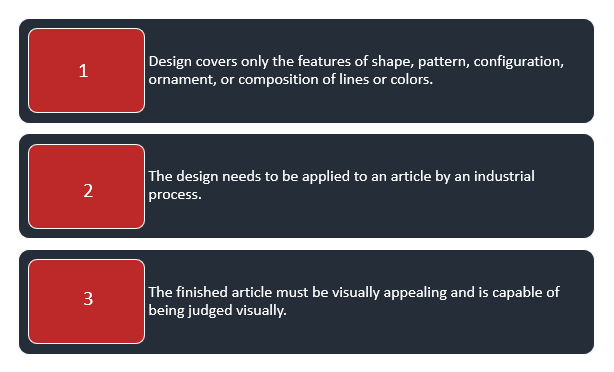

- As per Section 2(d), a design would be considered registrable if it fulfills the conditions described in the figure below:

Attention is particularly drawn to the definitions prescribed under the Act. For instance, in 2014, Amazon Inc. filed an application for design registration under class “14-02” of the Act, entitled as “Graphic user interface for providing supplemental information of a digital work to a display screen”. At the time of filing the application, the Design Rules granted protection to GUIs, however, the Controller of Designs decided that GUIs do not qualify for design registration as they do not satisfy the conditions of an ‘article’ and ‘design’ under the Act.

While rejecting Amazon’s application, the Controller enumerated some critical observations in the case. It held that:

- Mere consideration of the class number as prescribed in the design classification should not be the sole criteria for granting registration. The registration should also fulfill the definitions of ‘article’ and ‘design’ as under the Designs Act.

- Under the act, a design registration is not granted to a function of an article. A GUI or screen display, however, was considered as a function of a computer screen, which is operative only while the computer is turned on. Hence, it fails to fulfill the requirement of a design to have a consistent eye appeal under the definition.

- Screen displays are controlled by the function of an article, such as a mobile phone or a computer. They do not possess features of shape or configuration or other design parameters. Thus, a screen display cannot be considered as a ‘finished’ article judged solely by eye, and obtained through industrial process, as required by definition under the act.

- A GUI will not be considered as an article of manufacture as per the definition in the act, since it cannot be converted from physical input to physical output.

- As a GUI is not physically accessible, and cannot be sold separately as a commodity item in the market, it fails to meet the provisions of an article in the act.

Rationale behind the Controller’s Decision

The main rationale behind the Controller’s decision was: for a design to be eligible, it has to ‘consistently’ appeal to the eye and be capable of being judged solely by the eye. However, the design in the case of GUI becomes non-existent as soon as the electronic device is switched off. Therefore, a GUI fails to meet the criteria of a design as mentioned in the Act. This case has set an example for the Indian Design Registry and based on the same, the Registry continues to object the registration of ‘Screen Displays and Icons’ under class 14-04. Such arbitrariness in granting the design protection has become a real challenge for the companies and entrepreneurs looking to safeguard and monetize their designs.

Interpretation of the definition of ‘Article’ under Designs Act

According to the Act, to qualify for registration, a design has to be ‘applied’ to an article of manufacture and be capable of being produced and sold separately. In this regard, it is essential to refer to an authority which has been accepted by Indian courts and can be found in the case of Dover Ltd v Nurnberger Celluloidwaren Fabric Gebruder Wolff, wherein it was held that design is a conception or an idea as to features of shape, pattern, configuration, or ornament applied to an article, and not the article itself which is capable of being registered. It is a suggestion or form which is to be applied to the physical body of an article.

Accordingly, in the present context a GUI is applied to the component of an electronic device, i.e., the monitor or screen such as in the case of computer devices or smartphones etc. These devices as a whole and in components are articles of manufacture capable of being sold separately. Hence, a GUI, when applied to a monitor or display panel of a device fulfills the requirements of being an article under the Act and is capable of being registered as well. However, if registration is sought for GUIs alone, it is liable to be opposed, as it will not act as an article in itself. Hence, attention has to be paid while drafting the application of registration.

Interpretation of the Definition of ‘Design’

As reiterated above, a design must:

- Be applied to a specific article – In our case, this criterion is being fulfilled as the electronic device carrying the GUI is a specific article and the GUI is applied to the monitor or display panel of this specific device.

- Be applied to an article by an industrial process or means, whether manual, mechanical or chemical and, whether separate or combined – This requirement as well is fulfilled in our case. The electronic device as a whole is industrially manufactured and the processing unit of the device is an industrially manufactured fitted machine and which further applies the GUI (design) to the monitor or display screen (article). Therefore, the application of GUI to the display screens of the devices corresponds to applying design to an article.

- Be appealing to the eye and be capable of being judged solely by the eye, in the finished article – The GUI is an interface developed to be seen and judged by the eye. The idea behind developing a GUI is to render a visually interactive experience to the user where they can operate or command the device only upon seeing the interface. Consequently, for an efficient and differentiable experience, the software developers design GUIs to aesthetically appeal to the users. The design (GUI) is thus appealing and capable of being judged solely by the eye.

The requirement of the design to be applied on a finished article is also achieved here. In respect of electronic devices, an article is considered finished when that article can perform its intended function and can be sold. Therefore, in cases of electronic devices, the finished article is the ‘power/switched on’ article. Therefore, the GUI which is visible upon the switching on of the article is thus, being applied on a finished article capable of being sold.

Conclusion

From the above article, we can conclude that the Indian Design Office has set a superfluous deterrent to the protection of GUIs as a design. The opinion being taken as a precedent needs to be corrected.

The requirement of applying the design to an article can be achieved if a clear demarcation is made between the GUI itself on its own and the article to which it is applied. The GUI in itself is not the article nor does is satisfy the conditions of being an article. Therefore, the Controller’s objection against GUIs not satisfying the requirements of an article is restrictive and obstructive.

Another objection rationale by the Controller that the design has to be visible ‘consistently’ and not only when the gadget is switched on is inconsistent with the wordings of the Manual of Design Practices & Procedure which states that ‘Design features which are internal but visible only during use, maybe the subject matter of registration.’ Therefore, this objection is deemed to be rendered ineffective.

Furthermore, the present watertight perspective on registrability of GUIs as designs has made the 2008 Design (amendment) Act redundant. To match with international standards, it is imperative that design protection to GUIs be granted independently and the inflexible condition of its application to a physical object be done away with. A strong GUI protection framework is vital to prevent another case like Zoom VS JioMeet.

Sagacious IP research is one of the leading IP consulting companies in India and abroad. Our design filing and prosecution service have helped many clients to overcome the challenge associated with design especially GUI registration in India. Click here to know more about this service.

- Akash Dudhwa (India Filing & Prosecution) and the Editorial Team

Having Queries? Contact Us Now!

"*" indicates required fields