Top Landmark Cases that have led to a Robust Patent Prosecution System in the U.S.

U.S. patent laws and systems are certainly recognized as one of the world’s leading and most efficient systems. A few landmark cases have led to the evolutionary journey of the U.S. patenting system to attain perfection, thereby resulting in a robust and reliable method for granting high-valued patents.

In our latest article, we focus on an in-depth and comprehensive analysis of the current market and patenting scenario in the United States, along with the patentable subject matter under 35 U.S.C. 101 of the U.S. Patent Law and its exceptions. Read on to know more about the landmark cases that led to the creation and development of the great subject matter eligibility test that is critical to the understanding of the U.S. patenting system.

Table of Contents

Innovation – the Driving Force, Patenting – the Strong Foundation

Innovation has played a constructive role in the American economy all along. All innovative organizations operating in the United States have now recognized the need to protect their technical interests with strict patent laws. The precision and accuracy of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) have laid a strong foundation for businesses to thrive and provide a strong foundation for innovation protection. Over the past decades, the number of patent applications filed within the USPTO has increased significantly. Multinational companies consider the U.S. to be a true pioneer in the patenting system – based on the proven fact that U.S. patents are most valued and why every company considers filing in the U.S. as their primary geographical destination. The U.S. market not only targets established billion-dollar enterprises, but also provides a good starting point and framework for SMEs and start-ups.

The United States is a potential place for some of the world’s largest and most iconic companies. These enterprises have also had a large chunk of share in the American as well as the global patenting activity. Companies such as Google, Apple, Microsoft, IBM, and Amazon continue to apply for patents related to software domains. This is because software patents currently cover a wide range of technologies, such as Artificial Intelligence, BlockChain, Edge Computing, Virtual Reality, and Augmented Reality. In line with the latest technological trends, SMEs are also applying for more and more software patents. The result is an increased number of software-related patent applications filed with the United States Patent Office.

For a patent to be granted, the invention must constitute patentable subject matter under 35 U.S.C. 101, along with being useful, novel and non-obvious. Still, there has been a lot of variability in the IP world regarding the definition of such judicial exceptions for patentable and non-patentable subject matter. This is primarily specific to inventions related to the software field, or inventions mostly associated with computers. Consequently, there has been considerable uncertainty as to what type of claim or specific claim language the USPTO could accept for the subject matter to be eligible for a patent. Hence, it’s crucial to understand U.S. Patent Laws defining the innovation to be eligible for a patent. Let us familiarize ourselves with Sections 101 or 35 U.S.C. 101 of the U.S. Patents Act.

Defining 35 U.S.C. 101 of the US Patent Law

The USPTO has clearly defined (under the US Patent Law) what is patentable and what is not. Section 101 or 35 U.S.C. 101 of the U.S. Patent Act deals with subject matter eligibility for patenting. It states that a patent may be obtained for new and useful processes, machines, manufacturers, and compositions of matter. In addition, 35 U.S.C. 101 prohibits granting claims related to inventions that are judicial exceptions such as laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas.

Software patents have come under a lot of scrutiny in the past few decades in the United States and hence the road to patenting software innovations in the United States has not been smooth. This is because there have been several groundbreaking cases in the past few decades that have changed U.S. patent laws related to software patents. Meanwhile, these breakthroughs paved the way for innovation and encouraged companies to file more and more software applications in the United States. It can be tentatively said that some of the Supreme Court or Federal Circuit decisions in these cases put a hold over some of the claims that could be granted.

Today, software-based innovations are highly patentable in the United States. According to the recent decisions in some landmark patent infringement cases, software can be safeguarded in the U.S. if it is distinct and tied to a machine. The uniqueness of the software is determined based on whether it is novel and non-obvious, which are core patentability requirements for any idea or invention. More precisely, the software should essentially provide some sort of a technological improvement over the prior art and shouldn’t be something that can be done on a conventional computer.

It is important to note that the invention or idea that the applicant is trying to protect should not be an abstract idea. As per 35 U.S.C. 101, a claim constitutes patent-eligible subject matter if the claim is a process, machine, article of manufacture or compound. However, there are three judicial exceptions to the otherwise statutorily patent-eligible subject matter – laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas. The abstract idea exception applies to computer-implemented methods (i.e., software). Other than the concept of abstract ideas, the U.S. patent office prohibits inventions falling under categories of laws of nature and natural phenomena to be patented.

Top Landmark Cases and their Impact on U.S. Patenting World

Let us know review the critical landmark cases that have had a significant impact on the U.S. patenting system. It is to be noted that at least 10 Supreme Court cases have directly addressed the issue of patentable subject matter. The decisions related to these cases led to an evolution of the patentable subject matter requirements of the 35 U.S.C. 101 law. Some landmark cases that had the maximum impact on the U.S. patent system regarding U.S.C. 101 were – State Street Bank vs. Signature Financial, Bilski vs. Kappos, Mayo vs. Prometheus and Alice vs. CLS Bank. The decisions taken in these cases by the Federal Circuit and the Supreme Court have been monumental. These decisions aimed at limiting the number of patents that the USPTO shall grant and at the same time led to a surge in some specific types of patent applications, such as the business method applications after the State Street Verdict.

Landmark Case 1: State Street Bank vs. Signature Financial

The State Street Bank vs. Signature Financial in 1998 was a landmark case that gave decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit concerning the patentability of business methods. The federal circuit stated that the invention is patentable under section 101 as it explains that the transformation of data, representing discrete dollar amounts, by a machine through a series of mathematical calculations into a final share price, constitutes a practical application of a mathematical algorithm, formula, or calculation, because it produces “a useful, concrete and tangible result”- a final share price momentarily fixed for recording and reporting purposes and even accepted and relied upon by regulatory authorities and in subsequent trades. So, the federal circuit relied on the earlier precedent and stated that as long as the claim has a practical utility or which produces “a useful, concrete and tangible result” is not vulnerable under Section 101. In addition, the Federal Circuit determined that software programs that transform data are patentable subject matter under Section 101 of the Patent Act, even when there is no physical transformation of an article. The court emphasized that software or other processes yielding useful, concrete and tangible results should be considered patentable. Further, the court decision in the State Street Bank case made it clear to the masses that business method patents are patentable. This accompanied a massive increase in the number of business method patent applications in the United States.

Landmark Case 2: Bilski vs. Kappos

The United States Supreme Court ruled that Bernard Bilski’s patent application for hedging the seasonal risks of buying energy is an abstract idea and is therefore unpatentable. Initially, the Supreme Court had rejected the Federal Circuit’s holding in Bilski that the machine-or-transformation test is an absolute test for concluding the patent eligibility of a process. Rather, the Supreme Court held that the machine-or-transformation test is “a useful and important clue, an investigative tool, for determining whether some claimed inventions are processes under § 101 and not the sole test”.

The Supreme Court further said that the claims were directed to a basic process of hedging and hence termed it as an abstract idea and something fundamental in the world of financing; hence denying monopoly over an entire process. However, the decision did not clarify the basis for judging whether a particular process is abstract or not. In addition, it raised uncertainty about the patentability of business methods in the United States. Also, the computer-implemented software claims too came under scrutiny after the Bilski decision since the machine-or-transformation test was no longer considered to be the sole test for checking patentability under U.S.C. 101.

Landmark Case 3: Mayo vs. Prometheus

The next landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States came in the year 2012. This was the much talked about Mayo vs. Prometheus case. It specifically dealt with the use of natural laws and their implementation. The case set a precedent for future cases where natural laws are in play and implemented or utilized in some way or the other. In the Mayo vs. Prometheus case, the Supreme Court of the United States unanimously held that – claims were directed to a method of giving a drug to a patient, measuring metabolites of that drug, and with a known threshold for efficacy in mind, deciding whether to increase or decrease the dosage of the drug – were not patent-eligible subject matter. According to the Supreme Court, the act of administering drugs to a patient and measuring metabolites to determine whether the dosage of the drugs should be increased or decreased corresponds to a fundamental principle and granting monopoly over the fundamental principles is against the patent law.

As per the Supreme Court, the correlation between naturally produced metabolites and therapeutic efficacy and toxicity is directed to an unpatentable “natural law”. In addition, the first two steps of the claims were found to be not “genuine applications of those laws”. According to the Court, making such determinations was well known in the art and that the current process steps simply tell medical practitioners to perform a routine and conventional activity. The Supreme Court made clear about the use of natural laws and said that the claims that contain a law of nature can be patentable as long as the claim applies the law of nature rather than simply preempting it. This means that additional elements should be added to the claims beyond the natural law such that the entire process does not merely involve steps that are – well understood, routine and conventional. In conclusion, one can say that a newly discovered law of nature is unpatentable in itself and the application of newly discovered law is also unpatentable, if the application merely relies upon elements already known in the art.

Landmark Case 4: Alice vs. CLS Bank

The Supreme Court relied upon its decisions in the Mayo vs. Prometheus and Bilski vs. Kappos cases to pass another landmark judgment in the Alice vs. CLS Bank case in 2014. In this case, the patent at issue disclosed a computer-implemented scheme for mitigating “settlement risk”, i.e., the risk that only one party to a financial transaction will pay what it owes by using a third-party intermediary. In addition, the issue, in that case was whether certain claims about a computer-implemented, electronic escrow service for facilitating financial transactions covered abstract ideas ineligible for patent protection. Until this point, the software could not be patented unless it formed an element within hardware or a system. However, the software patents went for a toss after the Supreme Court ruling in the Alice vs. CLS Bank case.

The court observed that an abstract idea does not become patent-eligible by being implemented on a generic computer. The court used Mayo as a precedent and stated that an abstract idea could not be patented because it is implemented on a computer. The Alice vs. CLS Bank case verdict formed a suitable precedent for invalidating some of the more egregious software that seeks patent protection. The Alice Case had a great effect on patents for computer-related inventions, particularly software patents. Some important questions were left unanswered after the Alice case, such as – what test should the examiners adopt to determine whether a computer-implemented invention is a patent-ineligible abstract idea? Could a patent-ineligible subject matter be made patentable by the presence of a computer-related invention in a claim?

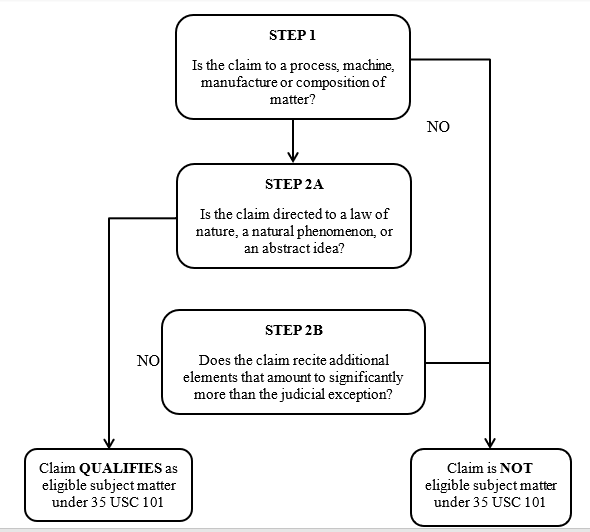

The Alice vs. CLS Bank, along with the Mayo vs. Prometheus case paved way for examining subject matter eligibility under U.S.C. 101. It also considered different approaches to conclude about patentability or non-patentability. As a result, the Supreme Court adopted a decisional approach under the Alice/Mayo framework, which provides a series of steps (Figure 1) in which the patent examiner, administrative tribunal or reviewing court has to answer a set of questions to determine whether the patent claim in question constitutes patent eligible subject matter.

The Alice/Mayo framework includes step 1, step 2A and step 2B. Step 1 requires the concerned reviewing authority to answer the first question. The first question is whether the patent claim covers an invention from one of the four statutory categories of inventions defined in 35 U.S.C. §101 (a machine, process, composition of matter, or article of manufacture). The Alice/Mayo framework is a simple yet complicated series of yes or no questions. The reviewing authority must move forward to the next step or the next question depending on the answer to the previous question. For example, at step 1, if the answer is yes, the reviewing authority must move on the next step (step 2A). Else, if the answer is no (i.e., meaning that the invention does not lie with the four statutory categories of invention), the reviewing authority must declare the claims to cover patent ineligible subject matter.

The Alice/Mayo framework truly initiate at step 2A where the reviewing authority is required to answer whether the patent claims cover one of the three specifically identified judicial exceptions to patent ineligibility. Currently, there are three judicial exceptions, namely, laws of nature, natural phenomena and abstract ideas. If the patent claim does not fall under any of the three judicial exceptions, the patent claim is said to cover patent eligible subject matter. Else, the reviewing authority must move on to the next inquiry if the patent claim covers any of the three judicial exceptions.

The third and final question which ultimately decides whether the patent claim will be rejected under 35 U.S.C. 101 falls under step 2B. Step 2B states that the reviewing authority must answer if the inventive concept that is covered in the claimed invention was “significantly more” than the judicial exception, or whether the claimed invention did not have “significantly more” and, therefore, was seeking to merely cover the judicial exception. If additional elements other than the judicial exception is not found in the claimed invention, then the reviewing authority moves forward with the 35 U.S.C. 101 rejections. Else, if the claimed invention adds significantly more and does not merely cover the judicial exception, the claimed invention covers patent eligible subject matter. The abstract idea exception occurs when the judicial exception is at play when computer implemented inventions are claimed. Until the end of 2019, the Supreme Court or the USPTO did not define “abstract idea”. As a result, U.S. Patent attorneys and professionals in the IP world were still not clearly aware of what invention is an “abstract idea” and what is not.

Final Thoughts

From the above discussed points, we can conclude that some inventions can surpass the abstract idea test and not all software inventions are necessarily abstract. It cannot be broadly held that all improvements in computer-related technology are inherently abstract and, therefore, must be considered at step two. There have been some improvements in computer-related technology which, when appropriately claimed, are undoubtedly not abstract. The Supreme Court of the United States has recognized the importance of software and its innovation potential. This has encouraged innovators to file more and more patent applications related to the software domain.

Therefore, it is of paramount importance for the patentees to clearly define and explain how an invention improves over the prior-art. This is crucial in the case of improvement in computer related technology. Therefore, years of patent prosecution in the U.S. have paved the way for greater clarity on patentability and have given birth to a credible and comprehensive patenting system.

Sagacious IP’s Patent Filing and Prosecution service enables enterprises to protect their inventions. Our highly skilled patent attorneys assist clients in preparing a strong patent draft that build their application for a smoother review process. Hence, it is wise to outsource the task of patent prosecution to an expert that has the desired skill set. Our team of registered Indian patent agents are adept in guiding businesses by offering them end-to-end support. Moreover, our collaboration with patent attorneys worldwide offers a technical finesse that can help companies and individuals make the right decisions. Click here to know more about our Patent Filing and Prosecution service.

-Dhruv Kaushik (Intellectual Property Prosecution) and the Editorial Team

Having Queries? Contact Us Now!

"*" indicates required fields